Retirement portfolios face a conundrum – they need enough equity risk to access the growth potential needed to increase the retirement pot, and reduced downside risk to help mitigate sequence risk.

So how can you maintain and reduce risk at the same time?

Identifying a defensive asset, not just a risk reducing one

Traditional portfolios use a range of defensive assets like government bonds, property and credit to manage upside risk, but these don’t always help against downside risk.

There’s a real difference between an asset that provides risk reduction and one that offers portfolio defence - and this is right at the heart of retirement investing.

What makes an asset defensive?

A lot of non-equity type investments are used as defensive assets, largely because they reduce volatility risk through a low or negative correlation to equities across the cycle.

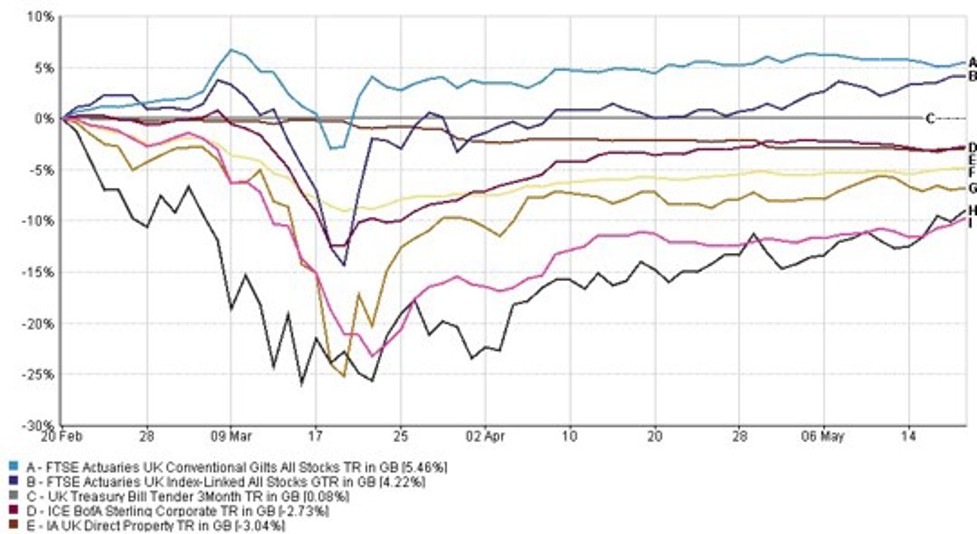

This is fine for accumulation, where volatility control is the key metric of risk. However, in drawdown, a reduction in downside risk is the measure of risk control that matters, especially in turbulent markets. As you can see in the chart below, during the start of the Covid sell-off in 2020, many ‘defensive’ asset classes offered no defence - just lower drawdowns:

Source: FE fundinfo, 20/02/2020 - 20/05/2020

Only Gilts (light blue) and Index Linked Gilts (dark blue) offered any sort of positive return during Covid, and even they briefly fell in value. To offer a noticeable reduction in portfolio losses, assets with potential for positive returns during risk-off are critical, i.e. those that can provide defence, not just risk mitigation or diversification.

Government Bonds are good, but not good enough to defend in drawdown alone

Government bonds (or gilts) remain the cornerstone of defence for most portfolios, having proved their worth through many periods of market stress.

In most periods of significant equity risk-off, there has either been a recessionary environment or an element of market dysfunction. Both situations need central banks to lower interest rates or give some form of liquidity injection, and both raise the price of government bonds.

However, there are two limitations to gilts as the sole defence in a portfolio:

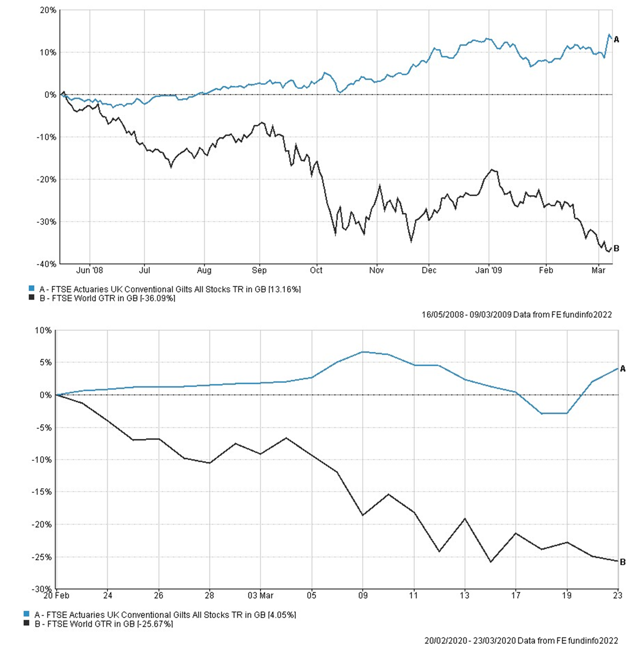

1. Return potential is dependent on the starting interest rate - when interest rates are high, central banks have more scope to cut rates and deliver significant upside for gilts. During the financial crisis of 2008/09, gilts rallied over 13%. However, when interest rates are very low (such as before Covid), gilts still provide protection, but the scale of that protection is moderated. At the peak of the equity risk-off in 2020, gilts were up less than 5%.

Source: FE fundinfo.

2. Gilts aren't guaranteed to offer protection all the time - we've seen during 2022 that there are times when gilts can fall in value at the same time as equities. While we see the fall in returns in 2022 as likely to be a once in a generation event, they’re a painful reminder of how portfolios can be hurt by the asset class that usually provides defence.

Volatility can complement gilts in offering defence during risk-off

There are few assets that offer true defence during risk-off. Gilts are one, Volatility is another.

Volatility as an asset class means positive exposure to the changes in equity volatility. So, when equity volatility goes up, the asset class goes up in value, and when it falls, the asset class falls in value.

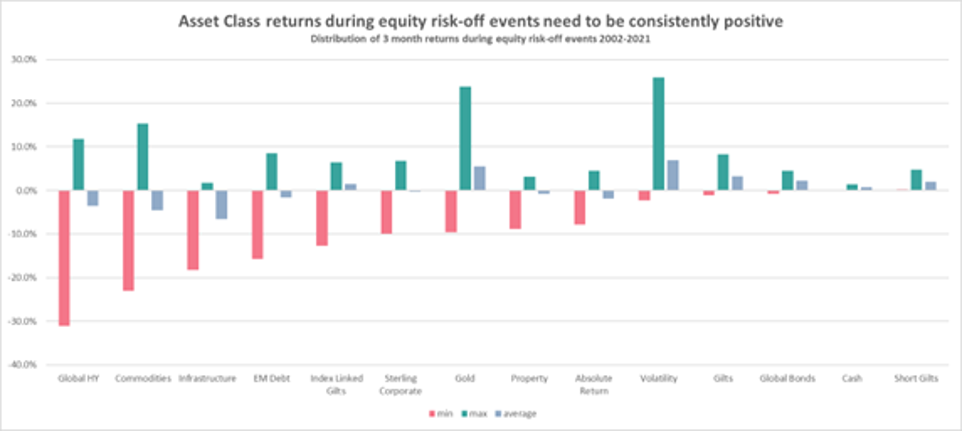

Historically, Volatility has offered the best and most consistent defence to significant equity risk-off events. Just look at the chart below. This shows the 3 month returns for a range of ‘defensive’ assets during the 30 most negative periods for equities between 2001 and 2021:

Source: FE fundinfo.

There are 3 key elements to note:

- Only 7 defensive asset classes listed here have a positive average return during these periods of risk-off

- Of those 5, only 2 (volatility and Gold) have a maximum return over 5%

- While Gold offers good defence, there are impediments to gaining explicit gold exposure in MPS portfolios, and it has a worst-case scenario of almost 10% loss over 3 months.

Considering volatility as an asset

- The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index (VIX) is the best-known measure of equity volatility. It’s an ‘uninvestable’ index that varies based on the size of daily moves up or down in US Equity share prices.

- Volatility is a signal of the markets’ fear and uncertainty about an asset’s value. Historically, at times of significant risk, volatility goes up. Because it’s derived directly from the movement in equity valuations, volatility is directly connected to equities.

- To invest in volatility, a fund manager must buy options on equities and hedge out the equity and interest rate risk, leaving just sensitivity to volatility. The cost of this is a drag on performance.

- Even before this drag, volatility is a zero-sum gain – what’s gained in return when volatility rises is given back when it falls.

What does investment in volatility fund look like?

Volatility investing has provided consistently high negative correlations to equities, and very large returns during risk off relative to traditional defensive assets.

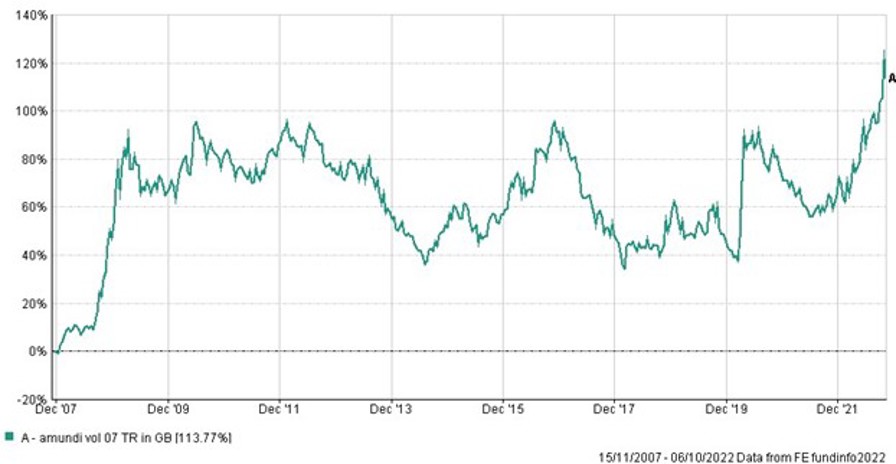

Below you can see the full history of returns from Amundi World Volatility – one of the longest running open-ended volatility funds.

Note the clear cycle of positive and negative returns:

Source: Performance data provided by FE fundinfo, over the period 31/12/2007 – 31/10/2022. Past performance is no indicator of future returns and investors could get back less than they put in. There is no guarantee the funds will meet their objectives.

Performance data is quoted from the fund’s NAV after the OCF has been taken. No other charges are included.

How does volatility fit within a portfolio?

Volatility works a bit like a hedge. It’s not a guarantee, but you pay a premium for the opportunity to see a potentially large upside at times when the equities in your portfolio are at their weakest.

There are two important outcomes to consider

1. During large market downturns, the size of the gains in volatility assets dampen portfolio downside risk compared to any other asset

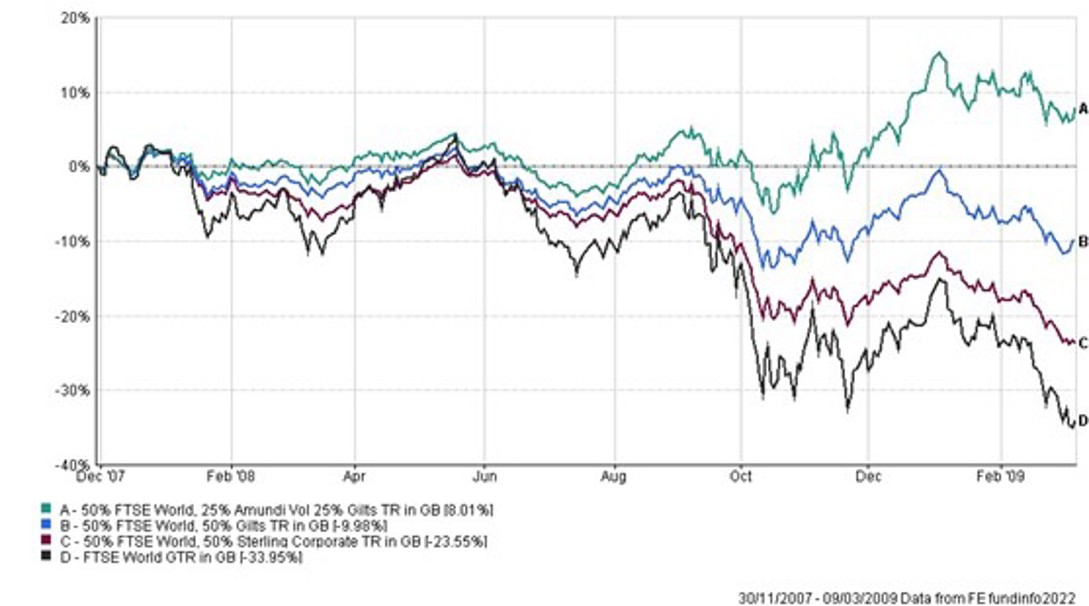

The chart below compares the FTSE World (D) to three basic portfolios, each with a 50% allocation to FTSE World as their growth asset, then different alternatives to assist with defence during the financial crisis of 2008/9.

-

- Line C (burgundy) shows the limited defence provided by a 50% allocation to Corporate Bonds at a time the Corporate Bond index fell almost 13%.

- Line B (blue) shows that a 50% allocation to Gilts did well, falling only 10% relative to the FTSE World’s drawdown of 34%, with Gilts themselves up over 10%.

- Line A (green) shows an allocation of 25% to Gilts and 25% to Amundi Volatility. The substantial upside from volatility meant that, at the lowest point, the portfolio was down only 6% while at the low point of equities it was up.

Source: FE fundinfo

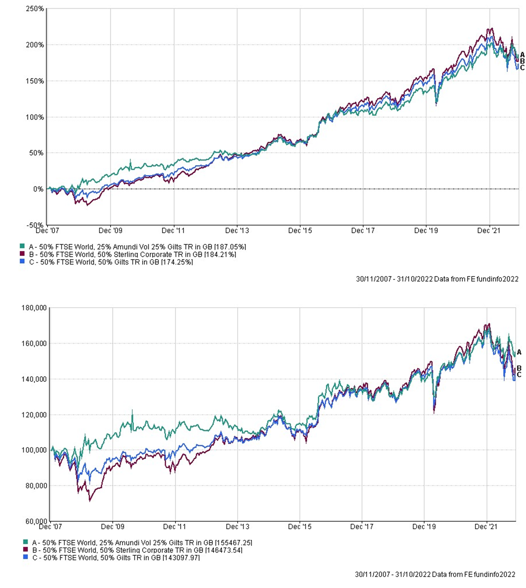

2. There’s a drag on portfolio returns.

Across a cycle, the drag on returns could be minimal or even non-existent, but it will depend on the timing of the investment.

If you invested in the above portfolios just before the financial crisis, the returns for portfolio A (the one with Amundi Volatility) would marginally outperform portfolios B and C. As a result, using portfolio A for drawdown would have led to noticeably better outcomes due to the relative limited exposure to sequence risk from the equity weakness.

Source: FE fundinfo

If you started investing at the bottom of the financial crisis, there is a performance lag from volatility and your pot size in drawdown would have been smaller. However, because the timing - while bad for the volatility asset - was at the low for equities, your pot outcome would have experienced substantial growth. In the context of retirement investing, both outcomes are a success.

In our view volatility is like no other asset in minimising falls in portfolio value. The cost of this hedge is the performance drag in the good times but over the long term the equity gains should outweigh this.

Back to the retirement conundrum

The key point to remember is the retirement conundrum - you want reduced downside risk while maintaining access to growth assets. Investing at the worst time for volatility leads to the largest lag in an extended bull market, but you’re benefiting from investing at the bottom of an equity sell-off - the best time to be investing in retirement, so those outcomes are more likely to be positive.

In summary

Volatility as an asset class changes the profile of returns for drawdown clients. Its inclusion seeks to smooth the journey, offering similar upside potential to a traditional drawdown portfolio, but with less potential for downside risk.

You can also listen to Tim discuss the benefits of volatility as an asset class in a recent Citywire podcast here.

This article is for financial professionals only. Any information contained within is of a general nature and should not be construed as a form of personal recommendation or financial advice. Nor is the information to be considered an offer or solicitation to deal in any financial instrument or to engage in any investment service or activity.

Parmenion accepts no duty of care or liability for loss arising from any person acting, or refraining from acting, as a result of any information contained within this article. All investment carries risk. The value of investments, and the income from them, can go down as well as up and investors may get back less than they put in. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.